You Are Here: Counselling > Info Base > Grief & Loss (page 1of 2)

Other Pages: Full Contents - About Me - Alcohol - Stress - Anxiety - Assertiveness - Depression - Tests - Home Page

In this section: Coping with Grief & Loss - Understanding Grief - Bereavement - Grief & Depression - Different Types of Loss - De-bunking stock phrases about Grief - Stages of Grief - Grief Encounter

Next Page: Common Symptoms of Grief - Coping with Loss - Could Counselling Help?

Grief is the word given to our experience following loss. It is a natural, instinctive and ages-old phenomenon, as old as humankind itself. It is thought by some to be unique to humans but there is evidence that animals also grieve. Elephants are noted as having elaborate grieving rituals and grief has been observed in species as diverse as geese, gorillas, dolphins, wild dogs and wolves. Many years ago, my cat unfortunately died and his long-time next-door playmate was so grief-stricken that a few days later, he lay down in the road in front of a car, seeming not to care as it ran over him.

The death of a loved one perhaps causes the most intense and enduring experience of grief. The idea that we will not see that person again is quite literally incredible - in other words we simply cannot believe it, especially at first. Gone. Forever. Yet that is just the start of it: the lives of those who survive the person who has died may have to change completely to take account of this loss. In my view, it is the biggest life adjustment that any of us can be required to make. Small wonder that many people need help with this process.

Unfortunately, in our modern Western society it can seem as if there is little time or space for that adjustment to take place. Wild animals can have elaborate and lengthy grieving processes and many ancient cultures likewise see bereavement as a lengthy process with well-established rituals. In Islam widows mourn for exactly four lunar months and 10 days. As the family mourns, they must avoid wearing decorative clothes or jewellery. In many estern European countries the wearing of black, especially by widows, extended for months, even years.

In contrast, the technologically sophisticated Western world often seems to require the bereaved to "bounce back" in a very short space of time. How long after the funeral do you have to be back at work? Typically a few days at most in my experience. Life goes on and there is the expectation when you meet people that you will be "normal". No one can tell simply from looking that you may have lost the most important person in your life. Moreover, without well-defined rituals to follow, how are people to know that they are grieving properly?

Moreover, even supportive and compassionate friends can be reluctant to talk about the death of a loved one after the funeral for fear of "upsetting" the bereaved. Many people often feel awkward and uncomfortable around the bereaved person. There is a terrible fear of somehow "getting it wrong" or "saying the wrong thing". As if anything could make you more upset than you already are if you are grieving! This is just one of the reasons why it can be helpful to talk to a counsellor. The counsellor won't mind what you discuss or how often you discuss it and the client does not have to worry about upsetting the counsellor.

Is grief the same thing as depression?

Although grief and depression have m any similar characteristics, such as sadness, anger, withdrawal and an inability to enjoy life, I would argue that grief is not depression, although grief-stricken people do sometimes go on to become clinically depressed.

Perhaps one of the things which differentiates grief or grieving from depression is that grief should perhaps be considered as a perfectly natural and understandable reaction to loss. In contrast, the origin or aetiology of depression may be more complex, Involving any number of factors, not all of them immediately obvious. Indeed depressed individuals may occasionally not have have anything obvious about which to be depressed.

Grief is not an illness; it is more usefully thought of as a part of being human and a normal response to the death of a loved one.’ Editorial in 'The Lancet' (medical journal) 18 Feb 2012

Although grief is commonly associated with the loss involved in a bereavement (i.e. someone you care about dying), grief can arise as a consequence of any loss. The following are examples:

- Relationship breakup

- Being diagnosed with an illness

- Loss of ability following an injury or illness (e.g. accident or stroke)

- Loss of financial security

- Miscarriage, stillbirth

- Death of a pet

- Loss of hope, ambition or a cherished dream

- Loss of a sense of security or safety after a trauma, like a car accident or being the victim of a criminal act

- The serious illness of a loved one, child or relative

- Loss of a friend or friendship

- Loss of fertility, childlessness

- Loss of a treasured possession, such as a family heirloom

Clearly, the more significant the loss is for you, the more intense will be your experience of grief. No one should judge how serious a loss is. Only the person concerned knows how significant it is. Some people think it is absolutely crazy to shed tears over the death of a pet but try saying that to someone who has just lost their faithful old dog who had been with them since their childhood.

Moreover, the grief response is emotional not rational. For example, you might be leaving one job to go to one which is better paid, has more prospects and is more interesting yet you can still grieve the loss of your colleagues or your history and experiences in that particular job. Even couples who cannot wait to be divorced can grieve the loss of hope, youth or innocence. Yes, honestly, some people do! Back to Top

Grieving is as individual as you are

Grieving is a personal and highly individual experience. And if you try to explain how you feel, other people may not understand it. You might find this frustrating or embarrassing and this can sometimes lead to a sense of isolation.

The way we each grieve depends on many factors, most especially our previous experiences of loss and how these were handled in childhood. Clearly, the nature of the loss also impacts on the grieving process: you probably would not grieve in the same way in response to losing an aged parent who was in poor health, as you would to losing a son or daughter.

Other factors that can influence your experience of grief include whether or not you have religious faith and the extent to which you feel supported by others around you as you grieve. Research has shown for example that those who are members of a community of believers, such as a church or a mosque, cope better and recover faster following a bereavement. Back to Top

Stock phrases about grief - are they true?

I wish I had a fiver every time a client told me that they had heard or perhaps felt one or other of the following stock phrases or "established wisdoms" about grief and grieving. Here are just a few and I have added my own comments and reflections

"Time is a great healer"

Actually, there is a lot of truth in this but saying it to someone who is feeling miserable is not a whole lot of help! Grieving is a process and yes, it does take time. How much time really depends on the individual. Quoting averages is dangerous because each situation is unique. However I would think of between 12 months and two to two-and-a-years as being a typical period of grief following the loss of a family member. That said, it can take much longer. The bereavement process following the loss of a child, even an adult child, can take very much longer than this.

Even many years after a loss, especially at special events such as a family event like the birth of a child, a birthday, etc, the bereaved person often experiences a powerful or painful sense of grief. This is entirely normal. Photo: Master Isolated Images

"You'll get over it"

Hmmm ... what does "get over it" mean? This is probably different if we are talking about the ending of a relationship with a "first love" than it is if we are talking about the death of a partner or a child. I would argue that there is always some residue following grief. The impact of that residue on our ability to lead our day-to-day lives varies tremendously. For example in the case of splitting up from my first love, I might be left with a few wistful feelings, some warm thoughts and a warm smile as I think about my sixth form girlfriend Jane. Thoughts of her may hardly ever intrude and then only in response to things which remind me of college. There is really no impediment on my day-to-day life. I fully accept that such things happen and I do not even begin to demand that things should be different.

If I think of my granny, who raised me from a young age, I can feel sad even now (years after her death) and wish that I could speak to her. Sometimes I can catch myself thinking "I've got a bit of spare time, I will pop in and see granny". Sometimes I feel sad, especially if I dream about her. But she was very elderly when she died and she lived a full and I believe happy life. I accept that everyone dies but not everyone gets to live to a great old age. I can be thankful therefore for her long life. I value and appreciate her influence on my young life and I can see how her many wise words and lessons have served me well. Despite my occasional sadness, there is no impediment on my ability to live a full life; rather the reverse, my life is richer for her having been there. In this case, "getting over it" means that I am in a place of calm acceptance.

What if I had lost one of my children? Thankfully I have not. Imagining I had, I can see that very many things would create thoughts which intruded into my day-to-day existence. Looking at other children for example, thinking of birthdays never enjoyed, or weddings or grandchildren. There would be a constant reminder of my loss. Yet my bereavement process, I hope, would have plateaued. That is to say, it would not be getting worse. My life would be tolerable and in the best scenario I would have moved to a place of reluctant acceptance and understanding in my reflection on my loss. The impact on my day-to-day life might however remain significant, most especially perhaps in terms of my relationship with my partner. Tensions might remain, assuming we were even still together because about 9/10 people experience irretrievable relationship difficulties following the death of a child. In short, I might not ever "get over it" in the sense that my life would be forever changed. A colleague of mine who has worked extensively with bereaved parents talks in terms of what she calls "a new normal" as being the best one can expect. It might never be as good as it was but what we hope for is that it can be "good enough".

In short then, the phrase "you will get over it" might have some truth in many cases but in some cases, "you will learn to live with it" might be a more appropriate goal.

I'm sorry but this is just complete rubbish. Grief can push the strongest person to their absolute limits. Crying absolutely does not mean that you are "weak". In fact, not expressing your emotions is far more dangerous from a psychological point of view than holding them inside. Research proved many years ago that people who keep their feelings to themselves or who cry alone are at far greater risk of a wide range of physical health problems. Any significant loss can have adverse physical health effects, but undisclosed ( or unacknowledged) feelings about loss double the risk of illness (King and Holden, 1998). Holding back on being who you are really is related to higher risks of both psychological and physical health problems (Gortner et al., 2006; Pennebaker et al., 2011) including breast cancer in women (Greer and Morris, 1975). Back to Top

"If you ignore it, it will get better"

No it will not. If you lock your feelings away and ignore them you have no chance to deal with them. In any case, they will only manifest themselves in physical illness or psychological problems, as described above. Grieving is a process. Unfortunately, it takes time. That time cannot be speeded up but it can be slowed down significantly if you refuse to acknowledge what you are feeling. Keep in mind also that what you feel in response to loss may be irrational, illogical, contradictory, even unsavoury or undesirable. Feelings are feelings. They do not always make sense. I have counselled many people who were the victims of abusive relationships and who, when they left their partners, did the most sensible and brave thing that they could possibly have done. Yet very often, sometimes even years later, they can become stricken with disabling grief when the abusive person concerned dies. It should not happen, it does not make sense, yet on an emotional and feeling level it does. Life is not like a financial spreadsheet where you can weigh up losses and gains and one offsets the other. Feelings simply do not work like this. If you feel you should not be grieving, think again. If you need to grieve, you need to grieve -- it is as simple as that and denying this is unhelpful, even dangerous, to your well-being. Photo by David Castillo Dominici.

They do not always make sense. I have counselled many people who were the victims of abusive relationships and who, when they left their partners, did the most sensible and brave thing that they could possibly have done. Yet very often, sometimes even years later, they can become stricken with disabling grief when the abusive person concerned dies. It should not happen, it does not make sense, yet on an emotional and feeling level it does. Life is not like a financial spreadsheet where you can weigh up losses and gains and one offsets the other. Feelings simply do not work like this. If you feel you should not be grieving, think again. If you need to grieve, you need to grieve -- it is as simple as that and denying this is unhelpful, even dangerous, to your well-being. Photo by David Castillo Dominici.

"I have not seen you crying, I didn't think you were that upset"

People often judge how someone is dealing with loss on the basis of their outward appearances, including crying. But crying is just one way of expressing emotions and it really is not a helpful measure of how upset someone is. Again, we are individuals and we all deal with loss differently. Remember also that crying is not proportional to how much grieving we are doing. Someone can cry a lot yet not have progressed very far in their process of grieving. Understanding someone's reaction to loss means being aware of the totality of their experience and their responses. For example, some people withdraw from life and deal with loss quietly on their own. Others need to go out and socialise, meeting with others in order to put their loss into some kind of perspective. Many people, particularly those experiencing an unexpected death, have a tremendous energy which they need to direct towards some cause or goal in order for their experience to have meaning. This is why bereaved people very often do charity work, or they set up some kind of fund, trust or action group in order to make sense of the death of their loved one. Back to Top

"I can see you have moved on to the _____ stage of grieving"

Popularised by Elisabeth Kubler-Ross in the 1970s, the “5 stages of grief” is for some people a helpful model which explains the processes they go through when they are dealing with loss. There is certainly some value in this model but there is also a danger that people assume that you should be going through a particular stage at a particular time and in a particular order. For example it is good to know that anger is a natural part of grieving and that being angry (especially with the person you have lost) does not mean that you are "a bad person"

The five stages are as follows:

- Denial: "This can’t be happening to me.”

- Anger: “Why is this happening?" "I blame the doctors for not spotting it earlier”

- Bargaining: “Make this not happen and in return I will ___.” or “What do I need to do in order to make this stop happening to me?” (found often following a diagnosis of serious illness)

- Depression: “I’m too sad to do anything”

- Acceptance: “I’m at peace with what happened”

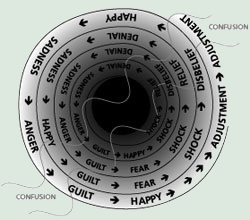

In my experience, people may or may not go through all of the stages. More interestingly, they may go back and forth between them. My own vision of the grieving process is that it is a kind of wheel of experiences through which we move and grow throughout the grieving period. It is always moving forward, or it should be, but we can re-experience different parts of the wheel nevertheless as we move forward through time and the wheel turns.

My own vision of the grieving process as a wheel which turns through a number of experiences as we move forward in time throughout the grieving period. Although moving forward, we may at times re-visit experiences from earlier in the process. Click image for large version. Illustration by the Author. Photo courtesy of Artur89.

Other 'models' of grieving also exist. In his excellent 1984 book "Living with Grief", the late Dr Tony Lake likens the grieving process to a large meal (like a buffet for example) which we cannot eat all at once. When we have had our fill we need to go away for a while and digest before returning for another course.

In 2003 my esteemed colleague (and the Daily Mail's 'Inspirational Woman of the Year 2013') Shelley Gilbert founded a charitable organisation called "Grief Encounter" which specialises in helping bereaved children, even if those 'children' are now grown up. Their website is a fantastically valuable resource for anyone facing these issues either personally or professionally.

In 2003 my esteemed colleague (and the Daily Mail's 'Inspirational Woman of the Year 2013') Shelley Gilbert founded a charitable organisation called "Grief Encounter" which specialises in helping bereaved children, even if those 'children' are now grown up. Their website is a fantastically valuable resource for anyone facing these issues either personally or professionally.

Shelley talks about the 'upward spiral of grief', in my view an eminently sensible and useful model which replaces definitive 'stages' of grief with a spiral model, somewhat more sophisticated than the one I myself use (described above). Shelley makes the point that "By using this spiral we can alleviate the pressure of having to move on through the 'stages' of bereavement. It may become less frightening to revisit these feelings time and time again. It does not mean that you have gone back to the black hole at the beginning.

She also questions the idea of 'acceptance' as a destination for the bereavement process. She says "The idea of acceptance can be misleading. We prefer to replace it with the word ‘adjustment’. If we bereaved are really honest, we rarely accept the loss. We learn to live with it; we change our life accordingly. But, accept? Hardly."

Next Page: Common Symptoms of Grief - Coping with Loss - Could Counselling Help?